Providers: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA/Metro); Southern California Regional Rail Authority (Metrolink); Port of Los Angeles; Amtrak

Modes: heavy rail metro; light rail; commuter rail; streetcar; intercity rail

Unique routes: 19 (7 Metrolink commuter rail; 5 Amtrak intercity rail; 4 Metro light rail; 2 Metro heavy rail metro; 1 Port of Los Angeles streetcar)

Distinctive stations: Los Angeles Union Station; Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center (ARTIC); San Bernardino's Santa Fe Depot

Equipment: Metrolink trainsets; Metro light-rail vehicles; Metro heavy rail metro vehicles; Amtrak Pacific Surfliner trainsets; Amtrak Superliner trainsets; Amtrak Horizon trainsets

So, after raving about passenger rail in Dallas-Ft. Worth, you're now telling me that the place more associated with the car culture than any other is not only more interesting from a passenger rail perspective than the Texas Metroplex but also the rail haven of Chicago? That's right.

In the last post, I attributed Chicago's relatively low ranking (see posts below) to the general uniformity of its L and Metra systems. Large and well-used, certainly, but not a lot of variety. Conversely, while the passenger rail options in the Los Angeles basin aren't as utilized as Chicago's historic networks, they offer rail observers a greater number of nuances, from vehicles and stations to range of modes and operational quirks. The pace of the region's passenger rail growth over the past three decades warrants its inclusion on this list.

Of course, L.A. wasn't always dominated by cars and highways. It's famed Pacific Electric Red Car streetcar and interurban network was considered by many to be the finest in the world until its demise in the 1930s and 40s, and numerous, premier transcontinental trains made Southern California their western terminus. Intercity rail service also extensive throughout California. You know what happened from there: passenger rail in all forms became unprofitable and scaled back as California pioneered the freeway concept and air travel became more accessible. When Amtrak was created in 1971, only a handful of long-distance and intercity trains remained. Not a single local rail transit route survived.

A full half-century went by as the region's population grew along with staggering congestion on roads and highways and smog conditions that ultimately led California to create some of the world's more stringent auto emissions standards. While plans for differing forms of rail transit in Southern California emerged even before the Pacific Electric's demise, it wasn't until the formation of the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission in 1976 that full-fledged proposals for a modern passenger rail network began to take root. Corresponding funding didn't materialize until 1985, when construction started on the first two lines that form the heart of today's MTA rail system: the Red Line heavy rail metro subway from Union Station to Westlake/MacArthur Park and the Blue Line light rail from downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach. The former would be the only subway operation on the West Coast outside of the San Francisco Bay Area (which you may hear about later in the Top 10) while the latter would utilize a formerly four-tracked Pacific Electric right-of-way, one of that network's main lines in its heyday. The Blue Line arrived first, with it's initial segment opening on July 14, 1990 from Long Beach to the fringes of downtown Los Angeles, with its loop through downtown Long Beach opening that September and its tunnel to Metro Center following in February 1991. With its subway tunneling delayed on several occasions by underground pockets of natural gas and extensive earthquake-proof infrastructure, the Red Line subway opened in 1993.

The two lines set off a flurry of MTA expansion projects that hasn't abated since. The Green Line light rail launched in 1995 between Norwalk and Redondo Beach – intersecting with the Blue Line at Willowbrook but never coming close to downtown Los Angeles, traveling in the median of the Century Freeway (Highway 105) most of its length. Although a short connecting track links the two routes near Willowbrook, the lines are essentially operated independently, with the Green Line featuring entirely grade-separated right-of-way and utilizing mostly different vehicles, while the Blue Line functions like many light-rail lines elsewhere – sharing roadways with automobiles and stopping often in the heart of the urban cores of L.A. and Long Beach. The Blue Line is one of the most heavily-used single light-rail lines in North America, with more than 87,000 average daily riders.

The Red Line was continually expanded through the late 1990s and early 2000s, as the Purple Line joined it in 1996 to operate a new spur subway line to Wilshire/Western and Red Line expansions ultimately reaching North Hollywood in 2000. The Gold Line light-rail connected Union Station with Pasadena in 2003 via a former Southern Pacific corridor and was extended to L.A.'s Eastside in 2009. Another light-rail route – the Expo Line – followed another abandoned Pacific Electric line from the Blue Line's Metro Center terminus past the University of Southern California (USC) to Culver City in 2012. The Expo Line is currently under final testing to extend to the Pacific Ocean in Santa Monica, with service expected to begin in early 2016. A similar expansion of the Gold Line from East Pasadena through the so-called Foothills Cities of Monrovia, Azusa, Glendora, Pomona, Clairmont and Montclair is also under construction, with the first phase to Azusa also expected to open in 2016. Another trio of projects are also currently being constructed: the long-awaited Purple Line extension westwards towards Westwood opening in phases beginning in 2023; the north-south Crenshaw/LAX light-rail line connecting the Expo and Green Lines via Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) due in 2019, with a possible northerly extension to reach the expanded Purple Line; and downtown Los Angeles Regional Connector project to connect the Blue, Expo and Gold Lines to allow through-routing of trains from Montclair to Long Beach (which will be one hella long ride) and Eastside to Santa Monica, adding two new downtown L.A. stations in the process. Completion of the new light-rail subway route is expected in 2020. All currently under-construction routes are supported by investment from the ambitious Measure R ballot initiative approved by voters in 2008. A number of additional projects are proposed or planned throughout the region, although a new round of investment would need to be approved by voters.

Around the same time the MTA's heavy rail metro and light-rail network was assuming some of the routes of the Pacific Electric legacy, another entity was at work preparing Southern California for a commuter rail system utilizing active and abandoned railroad lines extending far beyond downtown Los Angeles. Five counties established the Southern California Regional Rail Authority in 1991 to purchase 175 miles of rail lines from the Southern Pacific and access to Union Station from Union Pacific. Service began on three routes in 1992, ultimately growing to today's seven-route, 388-mile network serving 55 stations and carrying more than 40,000 daily riders. Lines owned by the rail authority see very frequent weekday service as well as more limited off-peak, reverse-commute and weekend options, while those operating on freight-owned routes provide less-frequent operations. Like the MTA's network, additional extensions and routes are possible, with a 24-mile expansion of the 91 Line to Perris currently under construction with service expected this December. In Oceanside, Metrolink connects with the North County Transportation District's Coaster commuter rail and Sprinter regional rail lines to San Diego and Escondido, respectively (see more on San Diego in the Runners Up post below).

The crown jewel of the Los Angeles region's passenger rail infrastructure is the signature 1939 Union Station. While not the bustling palace of celestial wonder that is New York's Grand Central Terminal or the stout and monumental Washington Union Station, Los Angeles Union Station is decidedly California, with its mission-style exterior and art deco interior. It's padded leather chairs are the perfect spot to sit and let the world go by while its outside courts and gardens allow peaceful escapes from the hustle and bustle of travel. Serving as the central connection point between the MTA's Red, Purple and Gold lines, six of Metrolink's seven lines and Amtrak's Pacific Surfliner, Coast Starlight, Southwest Chief, Sunset Limited and Texas Eagle, a railfan can be mesmerized for hours with all the variety of routes and destinations.

Speaking of the Pacific Surfliner, it's the nation's second-busiest intercity passenger rail route (after the Northeast Corridor). It offers eleven daily roundtrips between L.A. and San Diego with a handful of additional trains heading south to Los Angeles from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara. Truly befitting of its name, the views along the Southern California beaches is some of the most picturesque on any regularly-scheduled intercity passenger rail line.

In stark contrast to Union Station's historic charm is the glassy, modern Anaheim Regional Intermodal Transportation Center (ARTIC), the largest new passenger rail terminal opened in North America since Amtrak's Albany-Rensselaer station in 2002. The sweeping facility opened last December to serve Pacific Surfliner and Metrolink trains and was also designed to accommodate California's future high-speed rail network as well as a potential streetcar to Disneyland and other Anaheim attractions. Meanwhile, preliminary engineering for a downtown Los Angeles Streetcar is also moving forward supported by a local funding mechanism approved by voters in 2012. In the meantime, streetcar fans and history buffs can ride the San Pedro Waterfront Red Car, a 1.5-mile former Pacific Electric line operating replica Red Car-style vehicles Fridays through Sundays.

A number of fine passenger terminals also dot the Metrolink network, with San Bernardino's grand 1918 Santa Fe Depot perhaps the most exceptional.

So, after raving about passenger rail in Dallas-Ft. Worth, you're now telling me that the place more associated with the car culture than any other is not only more interesting from a passenger rail perspective than the Texas Metroplex but also the rail haven of Chicago? That's right.

In the last post, I attributed Chicago's relatively low ranking (see posts below) to the general uniformity of its L and Metra systems. Large and well-used, certainly, but not a lot of variety. Conversely, while the passenger rail options in the Los Angeles basin aren't as utilized as Chicago's historic networks, they offer rail observers a greater number of nuances, from vehicles and stations to range of modes and operational quirks. The pace of the region's passenger rail growth over the past three decades warrants its inclusion on this list.

Of course, L.A. wasn't always dominated by cars and highways. It's famed Pacific Electric Red Car streetcar and interurban network was considered by many to be the finest in the world until its demise in the 1930s and 40s, and numerous, premier transcontinental trains made Southern California their western terminus. Intercity rail service also extensive throughout California. You know what happened from there: passenger rail in all forms became unprofitable and scaled back as California pioneered the freeway concept and air travel became more accessible. When Amtrak was created in 1971, only a handful of long-distance and intercity trains remained. Not a single local rail transit route survived.

A full half-century went by as the region's population grew along with staggering congestion on roads and highways and smog conditions that ultimately led California to create some of the world's more stringent auto emissions standards. While plans for differing forms of rail transit in Southern California emerged even before the Pacific Electric's demise, it wasn't until the formation of the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission in 1976 that full-fledged proposals for a modern passenger rail network began to take root. Corresponding funding didn't materialize until 1985, when construction started on the first two lines that form the heart of today's MTA rail system: the Red Line heavy rail metro subway from Union Station to Westlake/MacArthur Park and the Blue Line light rail from downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach. The former would be the only subway operation on the West Coast outside of the San Francisco Bay Area (which you may hear about later in the Top 10) while the latter would utilize a formerly four-tracked Pacific Electric right-of-way, one of that network's main lines in its heyday. The Blue Line arrived first, with it's initial segment opening on July 14, 1990 from Long Beach to the fringes of downtown Los Angeles, with its loop through downtown Long Beach opening that September and its tunnel to Metro Center following in February 1991. With its subway tunneling delayed on several occasions by underground pockets of natural gas and extensive earthquake-proof infrastructure, the Red Line subway opened in 1993.

The two lines set off a flurry of MTA expansion projects that hasn't abated since. The Green Line light rail launched in 1995 between Norwalk and Redondo Beach – intersecting with the Blue Line at Willowbrook but never coming close to downtown Los Angeles, traveling in the median of the Century Freeway (Highway 105) most of its length. Although a short connecting track links the two routes near Willowbrook, the lines are essentially operated independently, with the Green Line featuring entirely grade-separated right-of-way and utilizing mostly different vehicles, while the Blue Line functions like many light-rail lines elsewhere – sharing roadways with automobiles and stopping often in the heart of the urban cores of L.A. and Long Beach. The Blue Line is one of the most heavily-used single light-rail lines in North America, with more than 87,000 average daily riders.

The Red Line was continually expanded through the late 1990s and early 2000s, as the Purple Line joined it in 1996 to operate a new spur subway line to Wilshire/Western and Red Line expansions ultimately reaching North Hollywood in 2000. The Gold Line light-rail connected Union Station with Pasadena in 2003 via a former Southern Pacific corridor and was extended to L.A.'s Eastside in 2009. Another light-rail route – the Expo Line – followed another abandoned Pacific Electric line from the Blue Line's Metro Center terminus past the University of Southern California (USC) to Culver City in 2012. The Expo Line is currently under final testing to extend to the Pacific Ocean in Santa Monica, with service expected to begin in early 2016. A similar expansion of the Gold Line from East Pasadena through the so-called Foothills Cities of Monrovia, Azusa, Glendora, Pomona, Clairmont and Montclair is also under construction, with the first phase to Azusa also expected to open in 2016. Another trio of projects are also currently being constructed: the long-awaited Purple Line extension westwards towards Westwood opening in phases beginning in 2023; the north-south Crenshaw/LAX light-rail line connecting the Expo and Green Lines via Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) due in 2019, with a possible northerly extension to reach the expanded Purple Line; and downtown Los Angeles Regional Connector project to connect the Blue, Expo and Gold Lines to allow through-routing of trains from Montclair to Long Beach (which will be one hella long ride) and Eastside to Santa Monica, adding two new downtown L.A. stations in the process. Completion of the new light-rail subway route is expected in 2020. All currently under-construction routes are supported by investment from the ambitious Measure R ballot initiative approved by voters in 2008. A number of additional projects are proposed or planned throughout the region, although a new round of investment would need to be approved by voters.

Around the same time the MTA's heavy rail metro and light-rail network was assuming some of the routes of the Pacific Electric legacy, another entity was at work preparing Southern California for a commuter rail system utilizing active and abandoned railroad lines extending far beyond downtown Los Angeles. Five counties established the Southern California Regional Rail Authority in 1991 to purchase 175 miles of rail lines from the Southern Pacific and access to Union Station from Union Pacific. Service began on three routes in 1992, ultimately growing to today's seven-route, 388-mile network serving 55 stations and carrying more than 40,000 daily riders. Lines owned by the rail authority see very frequent weekday service as well as more limited off-peak, reverse-commute and weekend options, while those operating on freight-owned routes provide less-frequent operations. Like the MTA's network, additional extensions and routes are possible, with a 24-mile expansion of the 91 Line to Perris currently under construction with service expected this December. In Oceanside, Metrolink connects with the North County Transportation District's Coaster commuter rail and Sprinter regional rail lines to San Diego and Escondido, respectively (see more on San Diego in the Runners Up post below).

The crown jewel of the Los Angeles region's passenger rail infrastructure is the signature 1939 Union Station. While not the bustling palace of celestial wonder that is New York's Grand Central Terminal or the stout and monumental Washington Union Station, Los Angeles Union Station is decidedly California, with its mission-style exterior and art deco interior. It's padded leather chairs are the perfect spot to sit and let the world go by while its outside courts and gardens allow peaceful escapes from the hustle and bustle of travel. Serving as the central connection point between the MTA's Red, Purple and Gold lines, six of Metrolink's seven lines and Amtrak's Pacific Surfliner, Coast Starlight, Southwest Chief, Sunset Limited and Texas Eagle, a railfan can be mesmerized for hours with all the variety of routes and destinations.

Speaking of the Pacific Surfliner, it's the nation's second-busiest intercity passenger rail route (after the Northeast Corridor). It offers eleven daily roundtrips between L.A. and San Diego with a handful of additional trains heading south to Los Angeles from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara. Truly befitting of its name, the views along the Southern California beaches is some of the most picturesque on any regularly-scheduled intercity passenger rail line.

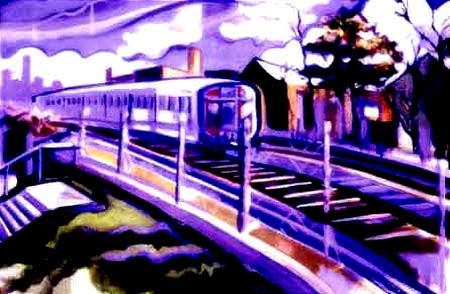

In stark contrast to Union Station's historic charm is the glassy, modern Anaheim Regional Intermodal Transportation Center (ARTIC), the largest new passenger rail terminal opened in North America since Amtrak's Albany-Rensselaer station in 2002. The sweeping facility opened last December to serve Pacific Surfliner and Metrolink trains and was also designed to accommodate California's future high-speed rail network as well as a potential streetcar to Disneyland and other Anaheim attractions. Meanwhile, preliminary engineering for a downtown Los Angeles Streetcar is also moving forward supported by a local funding mechanism approved by voters in 2012. In the meantime, streetcar fans and history buffs can ride the San Pedro Waterfront Red Car, a 1.5-mile former Pacific Electric line operating replica Red Car-style vehicles Fridays through Sundays.

A number of fine passenger terminals also dot the Metrolink network, with San Bernardino's grand 1918 Santa Fe Depot perhaps the most exceptional.

The Most Interesting North American Rail Networks Series