Any coverage on the numerous streetcar projects in U.S. cities in regent years reads like a never-ending saga. There's usually politically turmoil, funding challenges, construction delays and philosophical debates about dedicated lanes (see RAIL #37 - ed). Some generate national exposure from both transit advocates and critics.

Counter to the typical drama of American modern streetcar systems is the story unfolding in El Paso, Texas, which is quietly rebuilding a portion of its historic network on a 4.8-mile system that will be of greater mileage than those in already open in Tucson (3.9), Seattle's First Hill (2.5), Atlanta (2.7), Washington, D.C. (2.2), Kansas City (2.2) and Cincinnati (3.6), and those forthcoming in Detroit (3.3) and Milwaukee (2.5). The network will feature two loops through El Paso's downtown and uptown districts, sharing rails for a stretch on Franklin Avenue.

Rather than purchasing new, modern streetcars that more resemble light-rail vehicles, the city – in partnership with the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority and $97 million in total investment from the Texas Department of Transportation – is restoring six President's Conference Committee (PCC) cars that ran in El Paso until 1977. The vehicles will feature paint schemes donned by the cars during the 1950s, 60s and 70s. PCCs still run in active transit service in routes in Boston, Mass., Philadelphia, Pa., Kenosha, Wisc., and San Francisco, Calif.

Construction of streetcar infrastructure began this past January – managed by Paso del Norte Trackworks, a partnership of Granite Construction and RailWorks Track Systems – and service is expected to begin in late 2018. Brookville Equipment Corp., is handling the restoration of the vintage streetcars, which were – admittedly – in pretty rough shape after sitting exposed to the desert air for decades.

“This is a project to encourage infill development, to encourage preservation of our historic neighborhoods,” said Peter Svarzbein, who represents District One on the El Paso City Council and initially proposed the concept in a grad school paper at the University of Texas - El Paso (UTEP). “This is a powerful gesture from our city to not just throw away, but to reclaim that history and show it off.”

Fares for the service will match Sun Metro bus routes and 1,480 daily riders are estimated to ride the streetcars. Future extensions are possible to reach the Medical Center of the Americas as well as across the Mexican border to Juarez, which once was connected to El Paso by streetcar. Such an extension would represent the only international rail transit service in North America.

Monday, October 31, 2016

Thursday, October 27, 2016

Commentary: WMATA is in Aerodynamic Stall; They Need to Nose Down

Over the past year or longer, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transportation Authority's (WMATA) Metrorail network has existed in a state of crisis, with maintenance failures causing accidents, derailments and a state of service best described as a nosedive. Confidence in the agency from elected officials and the general public is at an all-time low, ridership is plummeting and every problem seems to compound upon itself.

In the midst of this, WMATA is faced with a severe budget crisis that is likely to force additional service cuts and fare increases to close the gap unless area elected officials devote additional funds or propose a long-term, dedicated source of investment for the system.

When transit providers are roiled by severe ridership declines and budget shortfalls, they tend to act like an inexperienced pilot facing aerodynamic stall (or, the inability of an aircraft to maintain lift needed to keep it aloft). The required action when experiencing stall is to reduce the angle of attack (or point the nose of the plane towards the ground) and increase power to gain airspeed. Once sufficient airspeed is obtained, then the nose can be pointed upward again and climb out of the controlled dive.

|

| image: Ascent Ground Schools |

Of course, this seems counter-intuitive to the basic laws of physics and gravity: if my aircraft is having trouble flying, why would I want to hasten its path towards a possible crash? Unfortunately, this knee-jerk reaction has produced deadly consequences throughout the history of aviation, including the tragic crash of Colgan Air flight #3407 outside of Buffalo, N.Y. in 2009.

WMATA is currently experiencing the equivalent of stall and it's proposed reaction – hiking fares and slashing service at a time when the system is chasing away riders with its poor level of performance – is akin to pulling the plane's nose up during stall. It's perhaps logical – we need to close our budget gap, so we must add revenue and cut costs – in the same way that not directing a plane towards the ground when it can't fly is logical.

Instead, the agency should point its nose down and gain speed by at least maintaining current fares and levels of service. Charging customers more for an inferior product flies in the face of good decision-making. Even better would be to reduce fares to re-attract jaded riders. Perhaps enough riders will return to build additional revenue. WMATA has hardly been forthcoming about any economic analysis that suggests raising fares will produce enough revenue to offset losses in declining ridership numbers.

Mass transit - like WMATA's Metrorail network – is intended to be a volume business: many customers paying lower prices. Instead, these proposed solutions function like an elite product: fewer customers paying higher prices, a recipe for the transit equivalent of stall. Let's hope they pull up on the stick in time.

Thursday, June 16, 2016

The Ballad of Northfield, Minnesota: Promise and Pitfalls of Passenger Rail Plans

Minnesota’s Twin Cities – as much as any other region in

North America – currently represents the unlimited potential of passenger

rail in reinvigorating communities. New light-rail lines are stretching out in

all directions, Northstar commuter trains speed to Big Lake and eventually St.

Cloud in its namesake direction and the twin hubs of Minneapolis’ Target Field

and St. Paul’s Union Depot contrast brilliantly with modern and historic flair.

Streetcar routes are under discussion, as is restored intercity service to the

state’s other large cities in Duluth and Rochester. Securing enough investment

is always a challenge, but those concerns are almost always mirrored by exciting

questions like when will the trains start running?

Just 45 miles to the south, Northfield, Minn., is the type

of place just beyond the limits of passenger rail’s potential. Eagerly

anticipating robust links to the Twin Cities – and beyond – Northfield has the

sort of conditions that are natural qualifiers for passenger rail service along

with the kind of challenges that leaves such connections just out of reach. For

now.

The Promise of Rail in Small Town America

With a population of just over 20,000, Northfield has been

defined by two sources of activity since its founding in 1855: agriculture and

education. Its motto speaks to those realities: “Cows, Colleges and

Contentment.” The area’s field growers produce staples such as wheat, corn and

soybeans with numerous dairy and hog farms, while the liberal arts Carleton and

St. Olaf colleges enroll more than 5,000 students each year. At the height of

passenger and agricultural rail traffic before the 1950s, three rail lines

funneled trains into the city from the Twin Cities to the north and Red Wing to

the east, while just as many fanned out from Faribault, 13 miles to the south,

making the region a historic Midwestern rail pipeline.

Today, that legacy has engendered in Northfield a small

urban community that stands to enjoy a flourishing future with assets

increasingly desired by younger and older Americans alike: distinctive historic

housing stock on streets lined with mature trees; a unique, accessible town

center with small shops and restaurants; and stable employment centers like

education and health care to create and maintain well-paying jobs. Places like

Northfield offer more leisurely residential living for workers seeing a

contrast to the bustle of large urban cores like the Twin Cities, attract smaller

companies seeking lower operating costs, lure college students seeking that

college town vibe and invite city dwellers to journey out on a weekend or

evening for a community festival or a well-regarded restaurant or craft

brewery. But all those attributes depend on an comfortable and reliable way to

get there.

Council Member Suzie Nakasian represents Northfield’s east

side neighborhoods in the First Ward on the city’s council and is the body’s

champion for restoring passenger rail service to the area. In addition to her

role on the Council, she heads up the Central Minnesota Passenger Rail Initiative (CMPRI), a grassroots effort to build support for a series of routes

throughout the state’s central and southern regions. For Nakasian, the

intersection between mobility and community development is what makes passenger

rail so attractive for place like Northfield.

“Northfield has the perfect combination of assets and

opportunities to make rail service successful: proximity to a major urban area,

affordable housing, strong academic institutions and a vibrant commercial

district,” says Nakasian, during a visit to RAIL Magazine’s editorial offices

in Washington, D.C. “We have strong

needs to both move people to the Twin Cities – to commute to work, reach the airport,

attend sports and entertainment events, and more – and bring people here, for

our colleges, places to raise a family or come down for a festival or shopping

for things like antiques and art. Our travel demand is bi-directional.”

"Restoring passenger rail on the corridor serving Northfield and other communities would give people another option of travel in the southern metro and southern Minnesota, whereas today the only options are car and limited bus service," says Erik Ecklund, who administers the Support the Dan Patch Rail Line effort (read our full discussion with Ecklund – ed). "More people want to live close to transit, and communities with good transit options will thrive."

The Beginnings of an Intercity Rail Corridor

Beyond Northfield’s need and ability to produce passenger

traffic to the Twin Cities is a larger desire to offer intercity passenger rail

service on north – south corridors in the nation’s heartland. Amtrak’s current

long-distance routes linking Chicago and the west coast are oriented for

east-west service. In fact, the Coast Starlight between Seattle and Mississippi

is the only north-south Amtrak long-distance route train west of the Mississippi

River. The CMPRI advocates the introduction of new service from the Twin Cities

south through Northfield and Faribault into Iowa and Missouri to serve Albert

Lea, Mason City, Des Moines and, ultimately, Kansas City. When combined with

northward extension of Amtrak’s existing Heartland Flyer north from Oklahoma

City via Tulsa to Kansas City, Northfield could host rail service connecting

the Twin Cities to Texas’ Metroplex.

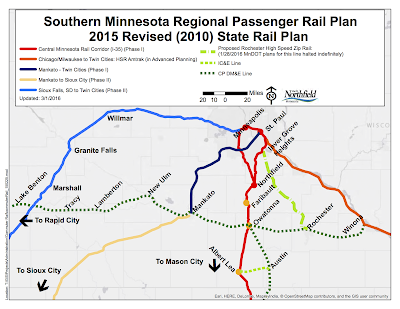

Myriad options of active and abandoned rail corridors (see above map) exist

throughout the Midwest to achieve a Twin Cities – Texas passenger route, as

well as new regional service within Minnesota. Several different paths are

possible between Northfield and Minneapolis or Saint Paul, while other lines

could bring new routes from the Twin Cities to Marshall and Rapid City or

Mankato and Sioux City. Additionally, Canadian Pacific’s lightly-used Dakota,

Minnesota & Eastern line offers an east-west option across Minnesota’s

southern tier, potentially linking Amtrak’s Empire Builder at Winona with

Rochester, Owatonna, Mankato and points west.

In 2015, the Minnesota Department of Transportation

identified the Central Minnesota Rail Corridor – the north-south route heading

south from the Twin Cities through Northfield, Faribault, Owatonna and Albert

Lea – as it’s top-ranked passenger rail option because of strong support for

service among elected leaders along the line. While Nakasian takes pride in the

route’s backing among her counterparts in neighboring communities, she believes

a rising tide lifts all boats for passenger rail options in central and southern

Minnesota.

“We feel strongly about the Central Minnesota Rail Corridor

as a practical option that could quickly produce numerous benefits to the

communities it would serve,” says Nakasian, who also notes the city recently

relocated its historic 1888 Union Pacific depot (see rendering at right) to a more optimal spot for passenger trains to stop in town. “We see it as the

first step in building momentum for a true regional rail network to connect

central Minnesota’s vibrant cities and towns.”

Pitfalls to Progress: A Racing Horse, Two State Senators and

Limited Funding

|

| Dan Patch: the horse that named a railroad |

Perhaps the most natural route for trains from Northfield to

travel en route to the Twin Cities is the so-called Dan Patch line. In 1907,

Minnesota entrepreneur Marion Willis Savage founded the Minneapolis, St. Paul, Rochester and

Dubuque Electric Traction Company, an interurban line stretching south and west

from Minneapolis through St. Louis Park, Edina and Bloomington and then tacking

to the southeast to reach Lakeville and Northfield. It became known as the Dan

Patch Line as Savage used it to promote his famous harness racing horse of the

same name, whom he stabled in the community that ultimately was called Savage

in his honor. The line was ultimately acquired by the Minneapolis, Northfield

& Southern Railway in 1918 after Savage and his beloved horse died within

days of each other. That railroad ultimately became part of the Soo Line in

1982, which, in turn, was then acquired by the Canadian Pacific Railway a

decade later.

|

| Dan Patch line courtesy of Support the Dan Patch Line |

|

| Dan Patch line courtesy of Support the Dan Patch Line |

But not long after the project appeared on

long-term planning documents, it disappeared from all official state plans

through the work of state senators William Belanger and Roy Terwilliger,

representing the Minneapolis suburbs of Bloomington and Edina, respectively.

Their 2002 legislation – Chapter 393, Sec.

85. Dan Patch Commuter Rail Line; Prohibitions – specifically banned any

formal study, planning or funding of commuter rail on the Dan Patch corridor by

MnDOT. The law effectively silenced any significant discussion of passenger

rail service on the corridor for more than a decade.

While Belanger and Terwilliger’s

ban may be seen as opposition from anti-transit hardliners, it moreso reflected

the sentiments of the communities they represented at the time. In 2002, Metro

Transit had yet to open the region’s first high-capacity transit line – today’s

Blue Line light rail from downtown Minneapolis to Minneapolis-St. Paul

International Airport and the Mall of America. The project was under discussion

for more than 15 years and many were skeptical about the entire concept.

Accordingly, Bloomington and Edina were in no hurry to install another new rail

mode – commuter rail – on a corridor that cuts through the hearts of

residential neighborhoods and commercial districts.

"Elected officials who are unsure or opposed to the Dan Patch Corridor should keep an open mind and remember that many people support this and times have changed dramatically since the legislative ban on this project in 2002," says Erik Ecklund. "Most of us have realized that we can't keep depending on the automobile for all of our travels and we need options. We also can't keep widening our roads to try to relieve congestion. The Dan Patch Corridor wouldn't just be a benefit to Minneapolis and the southern suburbs, but also southern Minnesota."

|

| High-capacity transit projects in the Twin Cities |

Beyond the state

prohibition on activity related to the Dan Patch line, the bigger obstacle to

momentum along the corridor has been the lack of investment opportunities to

support the region’s long list of transit capital priorities. From the time of

the 2002 legislation, popular support for new rail and bus rapid transit (BRT)

projects in the area has grown steadily as the Blue Line opened in 2004,

followed by the Northstar to Big Lake in 2010, Red Line BRT in 2013, and theGreen Line light rail connecting the Twin Cities in 2014. Currently, the

region’s most-desired projects – extensions of both the Blue and Green lines –

are struggling to receive investment from the state, despite having already

secured billions from local and federal sources. Simply put, the Dan Patch

corridor’s biggest challenge today isn’t from outdated legislation – which many

leaders along the corridor, like Nakasian, feel could be easily removed by

state senators currently representing the area, with Belanger and Terwilliger

having left the body. Instead, the route is too far down the list to have a

realistic shot at required investment, at least under the current framework for

distributing transit funding.

“We realize the

region has a long wish list of transit projects it hopes to implement,” says

Nakasian. “We feel we have a good case based on costs and benefits, but

pragmatically, there’s a number of communities that are waiting for their turn

ahead of us.”

Playing the Long

Game, But Hoping for More Immediate Results

Although returning

regional or long-distance passenger rail service to Northfield via the Dan

Patch line or another route is waiting for the right alignment of political

support and investment opportunities, Nakasian and other leaders waiting for

the trains to roll again point to how much has changed in recent years for

mobility options, both within the Twin Cities metropolitan region and society

at large. At the dawn of the millennium, new high-capacity transit routes in

Minneapolis and St. Paul were herculean tasks. Now, they can’t come soon

enough. At the same time, only the most prescient futurists could have

predicted real-time travel options powered by an app on a cell phone. The

point, according to Nakasian, is that things change quickly these days, and

change favors the prepared.

Labels:

commuter rail,

intercity,

Metro Transit,

Minneapolis,

Minnesota,

Northfield,

Twin Cities

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)