This is indeed a fair and perplexing question as, if most people have any perception of what high-speed and intercity rail is these days, it usually involves that stretch of railroad linking Boston in the north with Washington, D.C., in the south via New York City that's commonly known as the Northeast Corridor (NEC). That perception is likely based on the reality that the NEC is the most heavily-traveled passenger rail route in the Western Hemisphere and the only one in that same territory that comes close to reaching high-speed status.

Moreover, no other corridor in the nation is as suitable for high-speed rail, with five massive cities – Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington – and a handful of smaller ones – Providence, New Haven, Newark, Trenton and Wilmington – positioned less than 500 miles apart along its route, and populations in those areas who are the most accustomed of any in the nation to traveling by train. Airports all along the corridor – especially Boston's Logan, New York's Laguardia and J.F.K and Washington's Reagan National – are increasingly congested with international and domestic flights, while Interstate 95 that parallels the NEC often turns into a parking lot, and when it isn't is burdened by tolls for bridges, tunnels and the practically every mile of the highway in the State of Delaware. Because of that congestion, Amtrak's Acela and Regional trains on the NEC easily beat the travel time on I-95 between New York and Washington by well over an hour without significant traffic, are competitive with driving times between New York and Boston as well as shuttle flights on either half of the route when the downtown-to-downtown trip is compared.

As a result, a true high-speed operation on the NEC would have the greatest opportunity for success of any such project in North or South America. And yet, in the first round of high-speed and intercity rail projects selected by the Obama Administration under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act [ARRA] (see our analysis of those projects), four other corridors received more investment than the NEC, and the $700 million supplied to the NEC under ARRA will barely make a dent in higher speeds or increased train frequency, although its replacements of a couple bridges on the line will significantly reduce massive delays that sometimes occur on those bridges today. Critics of the Administration's decisions on these projects - such as Florida Congressman John Mica – claim more of the investment should have been directed to the NEC where it would have had the greatest impact. They have a point.

Meanwhile, a recent study by students at the University of Pennsylvania proposes a massive high-speed rail project in the corridor which would not only slice travel times to an hour-and-a-half between New York and Washington and only an hour-and-forty-five minutes between New York and Boston – mostly by constructing an entirely new line between Long Island and Boston, including a 20-mile tunnel below the Long Island Sound – but also offer six times as much frequency on the entire corridor. The price tag for such a massive effort: a cool $98.1 billion. Why would such a large amount of investment be necessary on a corridor that already carries so many passengers and hosts the fastest trains in the hemisphere?

That is because to label the service provided on the NEC high-speed rail would certainly be a misnomer, as trains reach truly high speeds (over 150 mph) on a very short stretch of track between Providence and Boston. Why is this the case, and what can be done to improve train performance on the NEC?

Like any good discussion involving passenger rail, the answer lies in its history. The NEC is today a single railroad – mostly owned by Amtrak, and by far its most significant physical asset – that was actually built by two separate railroads: the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad (usually shortened to the New Haven) from Boston to New York and the Pennsylvania Railroad from New York to Washington, D.C. These railroads didn't compete with each other so much as they both competed with the New York Central Railroad, so they offered connections between the two routes at the Pennsylvania's namesake station in Manhattan. In order to provide the fastest and most frequent service to New York City, both railroads electrified significant portions of their lines in the early-to-mid 1900s: the Pennsylvania its entire corridor between New York and Washington (as well as to Harrisburg) in 1935 and the New Haven its track from New York to New Haven in 1914. It is important to note the New Haven did not continue the electrification effort beyond its namesake city to Providence and Boston. The railroads utilized the best technology and equipment available to them at the time and built infrastructure most crucial to achieving higher speed operation: the elimination of all grade crossings via bridges and tunnels, and banked curves necessary to maintain higher speeds. For about a half century, the trains of the Pennsylvania and New Haven operating on these segments were the fastest trains in the world. That changed in 1964 when Japan debuted the Skinkansen – the Bullet Train – debuted at speeds reaching 125 mph, besting the 110 mph top speeds achieved by the Pennsylvania.

An entire account of the development of high-speed rail around the world isn't appropriate here, and as passenger rail became a perpetual money-losing proposition for the railroads after World War II, no further investment or upgrades were made on the NEC until Amtrak – with federal investment – began electrifying and rebuilding the route between Boston and New Haven. The project was undertaken to make possible today's Acela Express service, which began in late December, 2000.

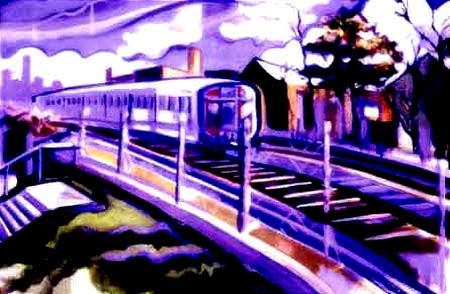

Thus, today's NEC is an amalgamation of essentially three different electrified railroads: Amtrak's Boston - New Haven segment; the New Haven's route between its hometown and New York – which today is owned by Metro-North Commuter Railroad, a division of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority; and the Pennsylvania's New York to Washington section, and Amtrak's Acela and other NEC trains operate very differently through these segments. Between Boston and Providence, the Acela hits its top speed – 150 mph – and is only slowed by congestion from other Amtrak and MBTA commuter rail trains. The infrastructure here – namely the overhead electric system (termed the catenary), signals, continuously-welded rails and concrete ties – is nearly as advanced as the best stretches found in Europe and Asia. South of Boston, trains are slowed by many sharp curves through Rhode Island and Connecticut, as well as 19 road grade crossings, which require trains to slow to 70 mph for safety. See photos to the left and below for a view of this section of the corridor.

Thus, today's NEC is an amalgamation of essentially three different electrified railroads: Amtrak's Boston - New Haven segment; the New Haven's route between its hometown and New York – which today is owned by Metro-North Commuter Railroad, a division of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority; and the Pennsylvania's New York to Washington section, and Amtrak's Acela and other NEC trains operate very differently through these segments. Between Boston and Providence, the Acela hits its top speed – 150 mph – and is only slowed by congestion from other Amtrak and MBTA commuter rail trains. The infrastructure here – namely the overhead electric system (termed the catenary), signals, continuously-welded rails and concrete ties – is nearly as advanced as the best stretches found in Europe and Asia. South of Boston, trains are slowed by many sharp curves through Rhode Island and Connecticut, as well as 19 road grade crossings, which require trains to slow to 70 mph for safety. See photos to the left and below for a view of this section of the corridor. South of New Haven, things get dicey. The New Haven electrified its line using a hybrid of catenary methods and equipment that never allowed for very fast trains at all. A full account can be found here. Today, that infrastructure is largely unchanged and is owned by Metro-North, which is mostly focused on the operations of its commuter trains between New Haven and Grand Central Terminal, not expediting Amtrak trains. Note the massively complex catenary structure left behind from the New Haven days through which the Acela must navigate.

South of New Haven, things get dicey. The New Haven electrified its line using a hybrid of catenary methods and equipment that never allowed for very fast trains at all. A full account can be found here. Today, that infrastructure is largely unchanged and is owned by Metro-North, which is mostly focused on the operations of its commuter trains between New Haven and Grand Central Terminal, not expediting Amtrak trains. Note the massively complex catenary structure left behind from the New Haven days through which the Acela must navigate.South of New York, the remnants of the Pennsylvania's electrification work still dictates how modern trains operate. While far simpler and more conducive to higher-speed operation than the New Haven's infrastructure – likely owing to the advances in technology between 1914 and 1935 – it still represents pre-World War II equipment and systems. Although the trackbed has largely been rebuilt with continuously-welded rail and concrete ties, the catenary is essentially the same railroad installed by the Pennsylvania more than 75 years ago.

Although heavier than typical high-speed trainsets employed in Europe and Asia – a result of Federal Railroad Administration crash-worthiness requirements – the Acela equipment built by a consortium of Alstom and Bombardier is not that far off that pace and could achieve top speeds of 165 mph for extended periods. However, subjecting the trains to operation over the disjointed and antiquated NEC infrastructure would be like driving a Lamborghini over a dirt road.

In all, the NEC – in its current state – is far short of high-speed rail infrastructure available in other nations. Indeed, even the 1965 Shinkansen – itself now 45 years old – was superior to the nearly ancient railroad that stands-in for true high-speed rail anywhere in the Americas at this point. Consider the latest high-speed line constructed in China, which is arguably the most advanced in the world today, although likely due to the fact that is the among the newest. When contrasted with the hand-me-down wires and tracks along the NEC, China's rail lines are simple, tidy and efficient, allowing for not only high speeds – their top route now reaches speeds up to 250 mph – but also allows for train frequencies of every 5 minutes. That level of service attracts more riders and also justifies the investment made in the infrastructure. Now, a comparison to the current work in China with high-speed rail isn't entirely a fair one to this nation or others, due to the vastly different governmental and economic structures in China that make such rapid mobilization of projects more achievable.

So, what can be done to improve the infrastructure in the Northeast to achieve better performance for its trains? The most achievable course of action would be public investment in new catenary equipment between New Haven and Washington, replacing the antiquated leftovers from the New Haven and Pennsylvania. However, two substantial complications would arise with such an effort. First, the project would significantly and negatively impact Amtrak and commuter rail service, complicating essential travel for work and business trips in the most dynamic business region in the county. Secondly, and more substantially, work would occur in six different states – Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland, along with the District of Columbia. As a result, organizing a structure by which investment would be channeled and work be prioritized would be difficult and contentious. For instance, although a substantial number of Acela passengers travel between New York City and Philadelphia, most of that trip takes place in New Jersey. Accordingly, New Jersey would be hesitant to invest its resources in a project that would not provide the most benefit to its state. Conversely, New York and Pennsylvania wouldn't be in a rush to fund upgrades to work done in their neighboring state. For this reason, such a project would need to be coordinated by the federal government and likely funding originating from that same source.

A more substantial project – such as the one proposed by the University of Pennsylvania's study – would certainly deliver massive economic and societal benefits that could positively reshape the entire region over a century or more. However, the costs of such projects are nearly impossible to realize in contemporary politics. The costs are so high because land must be acquired in some of the most highly-valued markets in the nation, and because such new infrastructure would require new bridges and tunnels with price figures in the tens of billions. Inasmuch as such a campaign of new infrastructure would be beneficial and ultimately justifiable, it would simply be unlikely to be undertaken due to its massive, upfront costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment