One of the recurring themes in all of literature is the struggle a writer engages with their native home. From Homer to Hemingway, authors across the ages have explored and reflected upon the influence of the place of their birth or upbringing. While this recurring archetype can cause out-sized coverage of the writer's formative community, it can also yield valuable insights and perspectives on the place's culture, traditions and identity that an outsider would have a hard time accessing.

With such a heady and theoretical opening, the direction this post is heading should be obvious: developments in passenger rail on your blogger's native turf, in this case news of a forthcoming study of expanding the light-rail system in Buffalo, N.Y. And, some context will surely be helpful in connecting this blogger with Western New York and its transit network.

Back in 1985, Buffalo opened a 6.4-mile light-rail line, connecting the city's downtown with the South Campus of the State University of New York at Buffalo (SUNY UB), which enrolls more than 29,000 students each year and is the largest university in New York State. Your blogger was aboard the very first day of service, and the experience sparked a lifelong passion and interest in community and public transportation, especially passenger rail.

The route – dubbed Metro Rail by the Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority (NFTA), the regional public transit agency which provides transit service in Erie and Niagara counties – marked Buffalo as one of North America's earliest adopters of the modern light-rail mode, following only Edmonton in 1978 and Calgary and San Diego in 1984 – predating most of today's larger light-rail networks in places like Portland, Denver and Dallas. Metro Rail was designed to revitalize commercial and retail activity downtown by serving residential neighborhoods in north Buffalo and its immediate suburbs, the college campuses of UB and Canisus College, and two hospital centers along the line. For a full background on Metro Rail, visit sites here and here.

Unique among modern light-rail systems is Metro Rail's 5.2-mile subway beneath Main Street, by far the bulk of its route miles (another 1.2 miles of the system operates above ground downtown in a pedestrian mall on Main Street, terminating at the First Niagara Center, home to the N.H.L.'s Buffalo Sabres). Among light-rail networks built after 1981, few utilize subway tunnels to the extent used in Buffalo. While a few short light-rail subway segments exist in St. Louis, Dallas, Portland and Los Angeles, subways were more common for hold-over light-rail operations, when lower construction costs made light-rail subways in viable in Boston, Newark, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Cleveland. A notable exception is Seattle's recent conversion of its downtown bus tunnel to accommodate its Link light-rail trains. And Ottawa is currently planning a new light-rail service that will construct a 1.5-mile tunnel through the downtown of Canada's capital city.

Buffalo ended up with a light-rail tunnel for several reasons. Planners had initially designed the line in the inverse of its current orientation, with a 1.2-mile subway downtown, and a 5.2-mile at-grade segment running in designated lanes above ground on Main Street outside of downtown. However, factors of geology in downtown Buffalo – particularly at the line's southern terminus at the city's waterfront – inflated the costs of tunnels downtown. Moreover, given that the light-rail mode was relatively new in North America, leaders at Canisus College and its surrounding neighborhoods were concerned about the appearance of overhead catenary wires through the campus. When combined, these demands necessitated flipping the plans, resulting in Metro Rail's current short surface, long subway configuration.

|

| 1980s rendering of Buffalo subway system |

It's within this context that Buffalo's Metro Rail light rail has existed since 1985, as a 14 station, 6.4-mile stand-alone route, averaging between 22,000 and 25,000 weekday riders, making it one of the best-utilized rail transit routes in North America per mile. Nonetheless, its role in revitalizing Buffalo is far less certain. The city's population plummeted after 1950, from more than 580,000 then to less than 300,000 today. And while much of that population shifted into nearby suburban communities, and Metro Rail certainly was not the cause of the population exodus – in fact, its consistent ridership counts are all the more impressive in that environment – commercial activity remained stagnant, at best, downtown, while its retail component largely vanished, and the two UB campuses remain unconnected but for sporadic bus service provided by the university. According to those measures, the service did not live up to its billing.

|

| Metro Rail at the South Campus station |

The current synergy of development in Buffalo has caused leaders at the local, state and federal levels to reexamine the original purpose of Metro Rail: to connect both UB campuses with downtown. As reported yesterday by the Buffalo culture and urbanism blog, Buffalo Rising, New York's U.S. Senators Charles E. Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand announced the Federal Transit Administration awarded the NFTA $1.2 million to conduct an alternatives analysis on the transit corridor between the UB North and South campuses. The award marks the first occasion since the original Metro Rail project that federal funds will support the study of a high-capacity transit corridor in Western New York. As part of the federally-required alternatives analysis process, the study will examine a series of options for the corridor, including no-build, minor improvements, and bus and rail capital projects. The NFTA will jointly conduct the study with the region's metropolitan planning organization, the Greater Buffalo-Niagara Regional Transportation Council.

While it's possible the study process will determine any of those options – including no build or incremental improvements, along with bus-focused service, like bus rapid transit – is the most desirable use of public investment for the corridor, an extension of Metro Rail to the North Campus in Amherst has strong merits as well. Most significantly, it would allow a one-seat trip between the North Campus, the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus and downtown Buffalo, and more fully utilize the community's existing asset of the Metro Rail infrastructure, including its high-speed subway tunnels. Additionally, two of the three most likely alignments for a light-rail extension to Amherst would also provide a one-seat train ride between the North and South campuses (I'll explain the differences between the three likely alignments shortly). Moreover, Metro Rail would allow for the greatest capacity, frequency and speed service within the corridor, most easily attracting UB students, faculty and staff, along with the larger community who could access new stations along the route. Lastly, an expanded Metro Rail system would set the stage for additional routes along existing, publicly-owned rights-of-way, enhancing overall mobility and making Western New York a more attractive place to live and work, potentially reversing population trends.

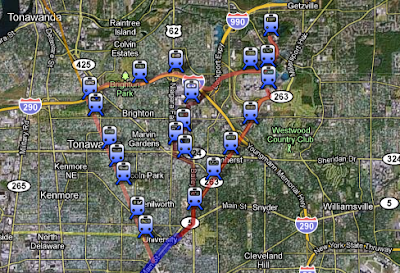

Most intriguing of any alternatives analysis process are the specific alignments under consideration. We'll stick to the light rail options here, due to the benefits explained above. There are three options likely to be explored are based on the original plan for the North-South campus connection, the most direct roadway right-of-way between the two locations, and utilizing a former rail right-of-way already owned by the NFTA. The Google Maps image below provides visual background for the descriptions below (click here to view the interactive map).

Option 1: Original Completion Alignment

The initial 1985 route between the two campuses was to continue from the current South Campus terminus underground below Main Street, then turn to follow Bailey Avenue heading north. The line would then emerge above ground using the naturally-occurring Onondoga Escarpment near Bryant Street. Although original planners did not include a station here, the intersection of Bailey and Grover Cleveland Highway would serve as an ideal location for a stop for the hamlet of Eggertsville, given the relatively high population density nearby. Tracks would then continue north along the west side of Bailey Avenue before turning left to cross Eggert Road near the intersection of Bailey and Eggert. The route would travel in parking lots of Northtown Plaza on the north side of Eggert and stop at a station there. Trains would then turn north on the unbuilt alignment for Marion Road, which continues as a residential street on the south side of Eggert. Trains would ascend an elevated structure to cross over the busy Sheridan Drive and stop at an elevated station serving the retail plaza at Almeda Avenue. Tracks would weave through parking lots and private right-of-way to reach the Boulevard Mall, the second-busiest mall in Erie County (after the Walden Galeria). Continuing on an elevated structure, the route would run parallel to Alberta Drive and cross over another busy thoroughfare, Maple Road. Again utilizing a combination of private easements and parking lots, the elevated route would stop near the Amherst Development Park on North Bailey Avenue, cross over that road and then climb over Interstate 290, near its interchange with Interstate 990. After crossing over I-990 proper and then Sweet Home Road, the tracks would descend into the grassy median of Audubon Parkway, and serve the UB North Campus at a station in that median. The tracks would continue in that median strip to reach a station for the campus' main dormitory complex and finally end its run at the Audubon commercial and governmental park.

Advantages: Planners devised this route in order to serve some of the region's largest activity centers, including major retail locations such as Northtown Plaza and the Boulevard Mall, along with a non-intrusive path to reach the North Campus. It would serve well-established residential neighborhoods in Amherst's Eggertsville community, and attract riders from the neighboring town of Tonawanda.

Disadvantages: There is no natural rail corridor to reach the North Campus from the end of the current route at the South Campus station. Consequently, the line devised by planners would require extensive use of elevated structures to cross several major thoroughfares and two interstate highways, while also claiming a significant amount of private property and easements through purchase and eminent domain power, substantially raising project costs and potentially causing hostility among the public.

Option 2: Millersport Highway Subway

With no natural rail corridor available, the most direct routing would be a continuation of the current subway from South Campus under Main Street and then Bailey Avenue as described in the first option scenario. However, here trains would not emerge from the tunnel at Bryant Street, but turn northeast underneath Grover Cleveland Highway (Route 263), which then is known as Millersport Highway north of Longmeadow Road. Like the first option, an Eggertsville station at Bailey and Grover Cleveland should be included, while stations underneath the intersections of Grover Cleveland/Millersport, Eggert and Longmeadow – known locally as Six Corners – and Sheridan Drive could serve nearby neighborhoods and small retail plazas. After passing underneath I-290, another station would be included at Flint Road to serve the commercial district there before the tracks leave the Millersport corridor to reach the North Campus, either above or below ground.

Advantages: A continuation of the subway underneath the Millersport corridor would be the most direct route to the North Campus, reducing trip times for the route. Also, less private property would need to be acquired, and the overall impact of construction would be far less disruptive than the first option.

Disadvantages: Although it was less densely populated and developed when planners were sketching out the Metro Rail route in the late 1970s, Millersport Highway was still the most direct route to the North Campus then as it is today. So why did they choose the more invasive, indirect alignment? Because while far more expensive than at-grade trackage, elevated structures are still far less costly than underground tunnels. With more than 3.7 miles of subway tunnels, the Millersport Corridor would likely far exceed the costs of the original alignment while also drawing fewer riders, especially when UB classes were out of session. These factors combined would lower the project's cost-effectiveness rating, and make attracting federal investment more difficult.

Option 3: The Tonawanda Spur

Instead of continuing from the current South Campus terminal, trains on this route would leave the subway tunnel just before the La Salle station and join a former Erie Railroad right-of-way currently owned by the NFTA. The corridor not only hosted Erie freight and passenger trains between Niagara Falls and Buffalo's eastern suburbs, but also separate tracks for the interurban trains of the International Railway Corp. As a result, the corridor is already wide enough to host two light-rail tracks, along with a parallel bicycle and pedestrian trail. Heading north-by-northwest, the route first passes a spur line that could eventually carry light rail trains west through north Buffalo, and then continues into the Town of Tonawanda. After a series of seven stations in the town, trains heading to the North Campus would then branch off the right-of-way and run alongside I-290, making stops at Brighton Park and Niagara Falls Boulevard before following the same alignment in option one to reach the North Campus.

Advantages: This option would utilize the existing tunnel turnouts near the La Salle station to reach the former Erie Railroad right-of-way, minimizing disruption to the existing Metro Rail operations. More importantly, it would take advantage of a well-defined and historic rail corridor through densely-populated neighborhoods, attracting riders while reducing construction impacts and avoiding costly elevated structures and tunnels (although very short segments of new tunnel would be needed near La Salle, and overpasses or underpasses may be required to cross busy arterials such as Kenmore Avenue, Sheridan Drive and Brighton Road). Also, installing light-rail infrastructure on the corridor would set the stage to continue the Tonawanda line north to the cities of Tonawanda and North Tonawanda and eventually to Niagara Falls, while opening the option of a north Buffalo spur route.

Disadvantages: Of the three options considered here, it is by far the least direct route between the existing Metro Rail route and the North Campus. By travelling primarily via Tonawanda and not Amherst, perhaps as much as 10 minutes of additional travel time would be necessary when compared to the previous two options. Additionally, it would functionally isolate the La Salle and South Campus stations, requiring passengers – especially students – to transfer trains at the current Amherst Street station to travel between the North and South campuses.

Assessment

There is no clear-cut favorite for how to proceed in extending Buffalo's Metro Rail to reach the UB North Campus. Each option has significant benefits and disadvantages to consider for policymakers and planners. Leaders at all levels of government should engage the Western New York community to determine its willingness to expand the system and what priorities it hopes to achieve with improved transit service.

Given the recent momentum the region has built in re-energizing its downtown, growing its medical campus and leveraging the value of the University of Buffalo, now may be the key time to take action. Competition for federal investment is always fierce, and those projects with the greatest positive impact on their communities tend to move forward. Extending the existing Metro Rail system to reach an important and growing educational institution is the type of distinguishing factor which could lead to future investment.