|

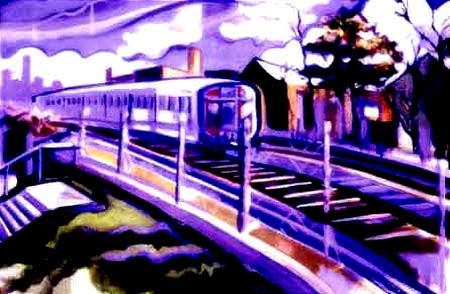

| Rendering of Denver's planned EMU vehicles |

Now, it is understandable why EMUs were generally not part of a restored family of commuter rail operations. They're expensive to install, meaning the electric catenary infrastructure they require demands up-front capital, and the vehicles themselves are more costly than their diesel-hauled counterparts. At times when every budget line item in capital projects are scrutinized, its far easier to justify the less-expensive diesel-powered trainsets, especially as double-deck passenger coaches became more common to meet capacity needs.

Those systems operating EMU trains today are but a handful, and most of those are hold-over services originally built by the private railroads of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Metro North Railroad operates EMUs over all three of its routes in New York and Connecticut – all of which serve Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan – as does its Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) counterpart, the Long Island Railroad, over substantial portions of its system. Across the Hudson River, New Jersey Transit hosts EMUs on several routes, while nearly all the regional rail lines of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) feature EMU technology. North of the border, the Agence Metropolitaine de Transport (AMT) – serving the Montreal region – is one of the most recent adopters of EMU trains, which were deployed on its Deux-Montagnes line in 1995. Chicago is the only site of EMU operations west of the northeast – which sees the trainsets operate over its Metra Electric division – as well as the venerable interurban, the South Shore Line between South Bend and downtown Chicago. Interestingly, one of the newest systems in North America does employ EMUs: the Errocarril Suburbano de la Zona Metropolitana del Valle de México, which began service between downtown Mexico City and Cuautitlán in 2008.

Aside from those half-dozen or so commuter rail systems, the rest of North America is largely devoid of electrically-powered commuter trains. Even several commuter rail operations along the Northeast Corridor which could operate EMUs under Amtrak's catenary infrastructure – the Penn Line of Maryland's MARC Train, Connecticut's Shore Line East service and the Providence/Stoughton Line of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) – do not run EMU trains and have no formal plans to do so (although MARC Penn Line trains are often powered by electric locomotives, unlike the others in this set).

Nonetheless, EMU technology does offer some significant benefits over diesel locomotive-based operations on the highest-capacity lines. Since a locomotive isn't hauling its own weight in addition to that of the trailing railcars and EMUs customarily don't power more than one additional coach, EMU trains are typically limited only by the length of the station platforms they serve and can achieve higher speeds than their diesel-powered counterparts. Moreover, for the same reasons, they are more energy-efficient while also producing more passenger revenue per trainset, since the passengers are – in essence – traveling in the locomotive itself. Lastly, EMUs produce no emissions directly from the vehicle, although the same is true for electric locomotives.

Mindful of this cohort of benefits, some current and future commuter rail systems are taking a fresh look at EMU technology and how it might be applied to their operations. The most likely to deploy EMU trains and infrastructure is the Eagle P3 Project in the Denver region. The project – a public-private partnership between the Regional Transportation District of Denver (RTD) and Denver Transit Partners – will build three new commuter rail lines serving Union Station in downtown Denver by 2016: the East Corridor to Denver International Airport (DIA); the Gold Line Corridor to Wheat Ridge; and a portion of the Northwest Rail Corridor to Federal Heights. All three projects will be electrified and operate EMU vehicles over their routes. Several renderings of potential EMU vehicles for the project have been developed (see below).

Along the same lines, plans are moving forward to electrify several of the existing routes of Toronto's commuter rail network, GO Train, as well as a spur route to Toronto's Pearson International Airport. To that end, Metrolinx – the transportation planning and policy-making entity in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) – recently approved recommendations for an initial round of electrification that would see the current Lakeshore and Georgetown lines add electric power, along with the airport spur off the Georgetown line. EMUs are expected to begin operations on the airport route by 2018, with the other lines following afterwards (see proposed map below).

Alternatively, one of the longest-discussed electrification commuter rail projects has been that of the Caltrain service between San Francisco and San Jose. The route – one of the longest continually-operating commuter rail services in the nation – operates high-frequency service along the densely-populated corridor and is an ideal candidate for electrification. However, two factors complicate fulfillment of these plans, one short-term and the other long term. First, Caltrain currently faces severe budget shortfalls due to recent economic challenges and California's state budget crisis, and will likely be forced to cut service and raise fares to compensate. Hardly stable conditions to undertake such an extensive effort. Moreover, the corridor will likely be the location for the high-speed trains of the California High-Speed Rail network. Should the route be selected, it is likely the entire corridor will be rebuilt, including the electric catenary infrastructure required for high-speed rail. With that upgrade, Caltrain commuter rail service would mingle on the route along with high-speed trains and require complete electrification to share the tracks. While construction on the initial high-speed rail segment in California's Central Valley will begin within the next few years, the timetable for the project to reach the Bay Area is undetermined.

In all, EMUs present notable operational and societal benefits as a result of their deployment, but require significant up-front capital to install their required infrastructure. Where the proper mix of demographics, rail corridors and investment are present, they should be studied as a valuable resource for both new and existing commuter rail operations.

Thank you very much for that extraordinarily first class editorial! Very creative and innovative one. Keep blogging.

ReplyDeleteLimo Long Island

Blog is a great place to update or to explore our idea and share a good things around.

ReplyDeleteAirport Limo Long Island