"What we're talking about is a vision for high-speed rail in America. Imagine boarding a train in the center of a city. No racing to an airport and across a terminal, no delays, no sitting on the tarmac, no lost luggage, no taking off your shoes. Imagine whisking through towns at speeds over 100 miles an hour, walking only a few steps to public transportation, and ending up just blocks from your destination. Imagine what a great project that would be to rebuild America."

The idea of coordinating connections between modes of travel at a central nexus – like a train station – is, of course, not a new concept by any means. Early in our nation's development, port cities found immense centers of travel activity near their docks and wharves. As the railroads stretched across the continent, train stations became the crux of community life in the smallest towns and largest cities. However, as travel by automobile and air emerged as the preferred modes of travel in the second half of the twentieth century, less priority was placed on organizing transportation options in a single location. This trend has begun to reverse itself, however, in recent decades, as new travel hubs uniting rail, bus, taxi, bicycle and pedestrian routes have been established – or reestablished in many communities.

Some commentators discussing how these intermodal facilities would amplify the opportunities offered by high-speed rail often describe a utopian-sounding environment where high-speed trains glide into a stunning glass atrium station to find frequent and easy to access connections to regional commuter rail and local rail transit – such as subways, light-rail and streetcars – alongside local and intercity bus service, taxi stands, bicycle racks or lockers and well-appointed pedestrian paths to reach nearby attractions such as central business districts or historical sites. These observers would prefer to position such a facility at or near a historical and well-maintained passenger rail station, too. Sounds like a pretty fanciful concept, eh? Maybe something more suited to a progressive European capital like Amsterdam or Prague, or perhaps possibly in that outside-the-box enclave of Portland, Ore? Except for the high-speed rail, all this is already happening in Sacramento, Calif.

Sacramento is one the nation's most historic railroading cities – after possibly Baltimore and Chicago – and perhaps the most important one in California. It was here that the legendary "Big Four" investors in the Central Pacific Railroad – Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker and Mark Hopkins, along with engineer Theodore Judah – launched the railroad that would connect with the Union Pacific at Promontory Point, Utah to complete the Transcontinental Railroad. Trains crossing the route would terminate here, before connections were established later on to reach the Bay Area and the San Joaquin Valley. The Central Pacific would ultimately become the Southern Pacific, which in turn was acquired by the Union Pacific in 1996. To recognize the city's prominent location as one of California's key railroad centers, the Southern Pacific constructed its Sacramento Depot in 1925. The architectural firm of Bliss & Faville designed the largely rectangular building in the Romanesque Revival style popularized by the famed H.H. RIchardson and similar to the Union Stations in both Hartford and St. Louis.

Today, the depot is known as Sacramento Valley Station and hosts as much, if not more activity than in its heyday. Four different Amtrak routes serve the station: Amtrak California's Capitol Corridor and San Joaquins, providing intrastate service, and the long-distance California Zephyr – connecting Chicago and Emeryville, Calif – and the Coast Starlight, which links Seattle with Los Angeles. All told, that's 40 weekday trains serving Sacramento (a couple fewer Capitol Corridor trains operate on the weekends). Moreover, the Capitol Corridor operates one of its daily roundtrips east of Sacramento to Placer County to reach Roseville, Rocklin and Auburn, heading into Sacramento in the morning and out in the evening to function as commuter service. The amount of traffic makes Sacramento Amtrak's second-busiest station in California after Los Angeles and more than 1.1 million Amtrak passengers traveled through the station in 2009.

And yet while intercity rail options in Sacramento are burgeoning, passengers connecting to or from these trains find themselves with substantial options to access the metropolitan region or elsewhere in the state. As part of its statewide rail program (note: please see our full-length feature article, "California's Railroad" in RAIL #11), a broad network of intercity bus routes are also operated. In Sacramento, Amtrak California bus routes head north to Medford, Ore, west to Fairfield and Suisun, and east to both Reno/Sparks and Lake Tahoe, Nev. Bus connections are coordinated to match Amtrak departures, especially so for the Capitol Corridor and San Joaquins routes.

Meanwhile, local transit connections at Valley Station abound. In December 2006, Sacramento's Regional Transit District (RT) extended its Gold Line light-rail to the station. Light-rail trains heading to Sunrise and others all the way to Johnny Cash's fabled Folsom stop on an adjacent platform to Amtrak trains. At the same time, RT's J Street bus routes (#s 30 and 31) call at the station. A taxi cue at the front entrance of the station offers additional options to travel through the city, and ample bicycle racks and space encourage non-motorized travel. Likewise, just a couple hundred feet away from the end of the platforms, a well-marked path guides visitors to the fine California State Railroad Museum and Old Sacramento State Historic Park. And given the station's position at the northwest corner of the city's downtown, nearly all of the central business district and state capitol office buildings are within walking distance (although the RT's light-rail and bus options would probably get you there faster).

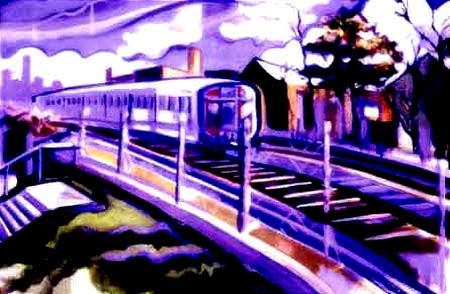

If Valley Station's claim as a model for intermodal locations wasn't already established, plentiful space exists on the north side of the existing station platforms to host a full-scale high-speed rail terminal. Land that used to support the Southern Pacific's extensive yards and shops (see photo to the left) now lies in wait for California's high-speed rail network to reaffirm the city's role as a rail hotbed. Corresponding with those efforts are plans to transform the former yards owned first by the Southern Pacific and later the Union Pacific into one of the nation's largest transit-oriented development projects. While work is just beginning, the project is expected to transform the Southern Pacific's Central Shops building into a public marketplace, offer expanded space for the Railroad Museum, include over 12,000 housing units and create 19,000 jobs. Projected to include at lease $5 billion in private investment, the project will include over 240 acres and last well into the next decade.

In all, Sacramento's Valley Station offers an outstanding example of achievement and opportunity in modern intermodal transportation facilities. It blends historical preservation with multiple and frequent service options in a location that is both convenient to existing activity and attractions, and nearby prime locations for new development. So, when detractors of well-designed intermodal facilities say "it can't be done," point them to Sacramento.

No comments:

Post a Comment