In the waning hours of 2012, I

posted an assessment of the 10 most exciting developments expected this year in passenger rail across North America. That, combined with my trip last December for the launch of

Amtrak service to Norfolk, has led me to ponder recently where might be the most exciting regions and corridors for new passenger rail in North America over the coming decade.

First, a few historical caveats are required. Many cities and regions already have dynamic and exhilarating passenger rail networks, and most of them will be enhancing and expanding those options over this same period. The legacy rail cities with multiple, interconnected modes (Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Toronto, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Chicago, New Orleans and San Francisco) will at the same time be strengthening their existing systems to achieve good repair status as well as opening new extensions.

In the metropolitan areas that introduced new operations – mostly heavy rail metros – in the second half of the past century (Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Montreal, Atlanta, Miami, the Bay Area, Vancouver and Mexico City), maintenance of the current service will be the priority, although new light-rail and streetcar projects will be incorporated to add additional capacity as local circulators. New commuter and regional rail lines may also emerge in these regions.

The least degree of momentum is likely to affect the wave of communities that were the first adopters of light-rail networks during the late 1970s and early 1980s: Edmonton, San Diego, Calgary, Buffalo, St. Louis, Monterrey and Guadalajara. San Diego has largely built-out its light-rail system to the greatest extent possible considering geographic constraints and is now awaiting a connection to California's planned high-speed rail network. In Alberta, although both Calgary and Edmonton have or will expand their light-rail operations with new lines and stations, but don't seem to be considering additional rail modes (

related RAIL coverage), although a high-speed rail link between the two regions is occasionally mentioned. Buffalo has never been inclined to add to its single 6.4-mile line given Western New York's massive population losses, although I discussed recent momentum on that front

in this post. Lastly, economic conditions and a lack of political consensus doesn't bode well for growth of the MetroLink network in the St. Louis region, although a

new streetcar project in the city itself is currently moving forward. Meanwhile, in Mexico, little resources have been available at all levels of government over the past several decades to support expansions of light-rail systems in both Monterrey and Guadalajara.

If I were writing this post a decade ago – and with the benefit of hindsight – the choices for most promising regions would have been obvious: the second wave of light-rail cities that massively expanded their networks over the past 10 years – Portland, Los Angeles, Dallas, Denver and Sacramento. The nation's largest light-rail systems all belong to this group, and have all added additional rail components ranging from streetcars to commuter rail and intercity routes to their local mobility mix over that same time period. And while all these communities will likely add new elements to their rail travel portfolios during the next decade, these are all also places where the value of passenger rail is now ingrained in the community.

So, where are the next hotspots for passenger rail options to become a lively and integrated aspect of community progress and pride? Here's my thoughts (in descending order):

10) A Tie?

The lowest spot here belongs to a half-dozen or so areas where rail could see a larger role in coming years, but momentum is presently tenuous and details unclear. Take Kansas City, where a new

streetcar project has been approved by local voters, but will have limited impact beyond its initial 2.2-mile route on Main Street in the city's downtown (

follow @kclightrail on Twitter for fantastic coverage of this project). The same is true in Cincinnati, where a

similar project should also begin construction this year, but has always faced stiff opposition by some (and vocal) elements of the community.

Oklahoma City seems poised to also jump aboard the streetcar bandwagon – as well as potentially expanding the popular

Amtrak Heartland Flyer route that terminates there to places such as

Tulsa, Wichita and Kansas City – but funding has yet to be secured for either effort. The Austin-San Antonio region has the most potential of this set of metropolitan areas – and Austin's

Capital Metrorail is gradually growing its ridership – but decisions on a

regional rail service and local

light-rail and

streetcar options always seem to be put off until later (

related RAIL coverage). The same seems to be true for the largest cities in Tennessee: Memphis has its

sturdy trolley network and Nashville its

Music City Star commuter rail line (

related RAIL coverage), but little has emerged to leverage those operations into a more cohesive presence for passenger rail in either place, let alone an

obvious intercity connection between them. Also worthy of some attention is perhaps a growing interest in passenger rail in Mexico, where the first of several planned commuter rail lines serving Mexico City opened in 2008, while the federal government recently accounted plans to launch several high-speed rail routes (

related RAIL coverage). Any or all of these communities could conceivably become the next rail trendsetter over the next decade, or just as easily stick with the status quo.

9) Detroit-Dearborn-Ann Arbor

Really? After relegating all these regions to wait-and-see status, you list the Detroit region as more promising than those?

Well, yeah. And here's why: there's no doubt that passenger rail projects in Detroit have all met a disappointing end over the past half-century. Sure, the elevated

People Mover is there, but it never has played a meaningful role in the city's mobility patterns and was even shut down for a period a few years ago, and the 2.9-mile loop only carries 2.5 percent of its 288,000 potential daily capacity on a regular basis. Moreover, a light-rail project on the city's Woodward Avenue was cut back from 9.3 miles to a 3.3-mile streetcar circulator service, dubbed

M-1 Rail.

Still, construction is scheduled to begin on M-1 Rail this year, and the state of Michigan is leading efforts to both improve

Amtrak's Wolverine service to Chicago and initiate

commuter rail between Detroit and Ann Arbor after agreeing to purchase the entire rail corridor from Kalamazoo to Dearborn from Norfolk Southern (

see this post for more information). Additionally, local leaders in and around Ann Arbor are advancing the

WALLY commuter rail project, which would launch commuter rial between Ann Arbor and Howell. The range and diversity of projects under various stages of planning and execution – along with bipartisan support ranging from Governor Rick Snyder to local mayors and county executives – suggests new perspectives towards passenger rail options are being cultivated in southeastern Michigan.

8) Orlando / Central Florida

Similar to Detroit and its surroundings, Orlando has long been a location of many passenger rail dreams, but little achievement. Multiple light-rail, commuter rail and even monorail and maglev proposals have come and gone, and the cancellation of the Tampa-Orlando high-speed rail project in 2010 served as the zenith of the region's struggles to install relevant rail options. But shortly after the high-speed rail project met its demise, the same governor who abandoned it ultimately approved the

regional SunRail service, which is now under construction and will open its first phase for service in 2014 (

related RAIL coverage). Already, the route is drawing substantial development interest around its station locations.

Additionally, the Florida East Coast Railroad's

All Aboard Florida effort moves closer to reality each day, with the railroad and governmental entities recently agreeing to lease right-of-way alongside the Beeline Expressway to connect Orlando International Airport with Florida East Coast's existing freight line at Cocoa. When fully implemented, All Aboard Florida is expected to provide hourly service between Orlando and Miami on three hour trips, competing with increasingly-congested highways.

Other rail operations are

also a possibility. The Florida Department of Transportation is expected to commission a study this spring on the

Orange Blossom Express, a 36-mile regional route from Orlando to Eustis over the Florida Central Railroad. Meanwhile, the Georgia-based company

American Maglev is investigating a potential $315 million maglev line between Orlando International Airport and the Orange County Convention Center. While these projects are theoretical – at best – at this point, the burgeoning list of projects points to a growing rail appetite in central Florida.

7) Ottawa

Positioned between Canada's two largest cities – Montreal and Toronto – the nation's capital will begin construction on its first full-fledged light-rail route this year. The 12.5-kilometer, 13-station

Confederation Line (

related RAIL coverage) will link the existing

O-Train regional rail line at Bayview through a downtown subway tunnel with the city's intercity

VIA Rail station, which offers multiple daily trips to both Toronto and Montreal. The service will bring direct rail transit service to the downtown of Canada's fourth-largest city, and improve mobility in the nation's most densely-population region. The Confederation Line will utilize the right-of-way of the city's existing busway, which is already operating above capacity.

6) Puget Sound

For a long time, I considered Seattle among the type of cities listed in number 10 above: many rail transit proposals, little progress in implementing them. Although

Sounder commuter rail to Tacoma and Everett offered solid regional connectivity, and

Amtrak's Cascades service linking Seattle to Vancouver, Portland and Eugene has long been among the nation's most well-conceived routes, the opening of the 15.6-mile

Central Link light-rail in 2009 along with the Seattle Streetcar to Lake Union in 2007 has transformed the image of rail transit in the Puget Sound region.

Already, construction on the

University Link extension is underway to reach Capitol Hill and the University of Washington by 2016. Likewise, the

East Link will link downtown Seattle with Mercer Island, Bellevue and Overlake, with construction beginning in 2015. Moreover, as many as five

additional streetcar routes have also been proposed throughout the city.

Elsewhere, Sounder service was recently extended south from Tacoma to Lakewood, as a former freight rail line has been upgraded to accommodate the new service, and avoid the windy, single-tracked BNSF Port Defiance route. The enhancement will also improve travel times and reliability for Cascades trains between Tacoma and Portland. Lastly, extensions are being studied for the 1.6-mile

Tacoma Link light-rail line, which opened in 2003, including a possible connecting with Central Link at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

5) Phoenix-Tucson

Not unlike Seattle, passenger rail in Arizona's largest cities has taken a while to come together. Various proposals were met with resistance from state and local officials and denials at the voting booth. In 2008, the 20-mile

Valley Metro Light Rail opened, connecting Phoenix, Tempe and Mesa. Ridership has far exceeded expectations, and a slew of expansions are in the works (

related RAIL coverage).

Meanwhile, in Tucson, the

Sun Link Modern Streetcar is currently under construction and is expected to open for service later this year (

related RAIL coverage). The 3.9-mile route will link downtown Tucson and the

University of Arizona campus. Substantial transit-oriented development projects are in the works in conjunction with streetcar stops.

With local rail transit options progressing rapidly in both metropolitan areas, the Arizona Department of Transportation is currently exploring a

regional rail service to connect both communities. Such an operation would likely resemble similar systems in the Mountain West,

Utah's FrontRunner linking Ogden, Salt Lake City and Provo and the

New Mexico Rail Runner Express, which spans Santa Fe, Albuquerque and Belen (

related RAIL coverage). Other commuter-oriented routes in and around Phoenix will also be considered as part of the study.

4) Research Triangle

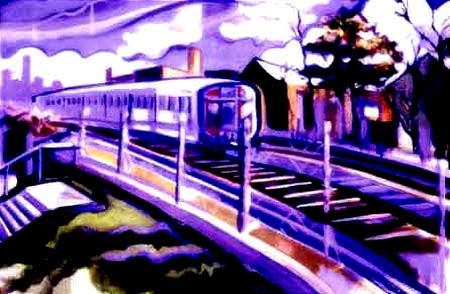

To me, the above rendering of

Triangle Transit's planned light rail and commuter rail routes serving downtown Durham speaks strongly of the potential of these emerging rail markets (

related RAIL coverage). Already, the core cities of the Research Triangle region – Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill – already benefit from intercity rail connectivity between the area and North Carolina's largest city, Charlotte, via Amtrak's Carolinian and Piedmont routes,

both supported by the state.

Light rail would connect all three cities, while regional commuter rail would broaden the reach of the network. In fall 2012, voters in both Orange and Durham counties approved sales tax levies to support construction of the

17-mile route that will link Chapel Hill and Durham. The region is still waiting on action from Raleigh County leaders to allow a sales tax referendum there, but the city of Raleigh is advancing plans for a

new Union Station to support future light-rail and commuter rail service as well as Amtrak's intercity trains.

|

| Tide light rail and Amtrak (middle-right) trains on opening day of Amtrak service |

3) Hampton Roads

As I mentioned in the intro, my most recent visit to Norfolk convinced me of the steadily growing importance of passenger rail in the Hampton Roads / Tidewater region. In less than a year, Norfolk has gone from no passenger rail options of any kind to both its vibrant 7.4-mile

Tide light-rail line and

Amtrak Northeast Regional service to Richmond, Washington, D.C. and Boston.

In the next few years, it's likely that additional Amtrak trains that currently terminate in Richmond

will be extended to Norfolk as additional capacity improvements are completed on Norfolk Southern's route between Norfolk and Petersburg, while

Virginia Beach explores whether the Tide route will be extended from its current endpoint at the Norfolk city line at Newtown Road along the same right-of-way, which was recently purchased by the city of Virginia Beach. Additional Tide expansions are possible elsewhere in Norfolk, as well as reaching neighboring cities in Hampton Roads, such as Portsmouth and Chesapeake (

related RAIL coverage):

2) Charlotte

North Carolina earns another top spot on this list through the strong efforts of its largest city, as Charlotte has spent the past half-decade reintegrating rail transit through its

LYNX light-rail route. The 9.6-mile line opened in 2007, and is drawing national acclaim for its strong ridership growth and TOD projects. Former mayor

Pat McCrory – a leading champion of the LYNX project – has now ascended to governor, and is expected to continue his strong support of passenger rail and transit, while current mayor

Anthony Foxx was recently nominated by President Obama to succeed

Ray LaHood as the next Secretary of Transportation.

Based on the success of the initial LYNX segment, a 9.5-mile northeasterly extension of the route will break ground this year to link the current terminus at 7th Street in Uptown Charlotte with the

University of North Carolina – Charlotte by 2017. Also, currently under construction is the first segment of the

Central City Corridor, a 9.9-mile streetcar line running east-west through the city of Charlotte and connecting with LYNX in Uptown. Also envisioned in the future is the 25-mile

Red Line commuter rail to connect Charlotte with Huntersville, Cornelius and Davidson, along with an additional 6.4 mile streetcar line to Charlotte-Douglas International Airport. A new intermodal facility to connect LNYX, streetcars, commuter rail, Amtrak intercity trains and

eventual high-speed rail is also under consideration.

1) Twin Cities

One of the common archetypes of the passenger rail renaissance over the past half century has been the trend of a metropolitan area or region – where an initial project met strong resistance – suddenly is transformed to a magnet for new lines and services, and communities and neighborhoods are lining-up to benefit from the next expansion. Such was the case in places like Portland, Denver and Denver, and more recently in Charlotte and Norfolk. This notion is most readily apparent in Minneapolis - St. Paul.

For years, the only passenger train rolling through the Twin Cities was Amtrak's daily

Empire Builder between Chicago and Seattle/Portland. Then the 12.3-mile

Hiawatha light-rail line (

related RAIL coverage) opened in 2004 between downtown Minneapolis, Minneapolis-St Paul International Airport and the Mall of America in Bloomington. The

Northstar commuter rail service followed in 2009 (

related RAIL coverage), spanning a 40-mile corridor between Minneapolis and Big Lake. And now, the

Central Corridor light-rail project is nearing completion between St. Paul and Minneapolis, which will terminate at the former city's recently-restored

Union Depot (related

RAIL coverage: "

Fresh Passenger Rail Approaches").

As many as six light-rail and commuter rail corridors have been envisioned to form a comprehensive regional rail transit network, with the

Southwest corridor to Eden Prairie currently receiving the highest priority. Minneapolis is planning to compliment the historic St. Paul Union Depot with its own intermodal facility dubbed

The Interchange, which is currently under construction and will open in 2014. New intercity routes such as the

Northern Lights Express to Duluth and Zip Rail (

fantastic website) to Rochester are also at various stages of planning and outreach, while the state explores options to link the Twin Cities with Chicago with

high-speed rail, either going through the rail-adverse Wisconsin or around it.

.jpg)