Providers: Chicago Transit Authority (CTA); Regional Transportation Authority (RTA/Metra); Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District (NICTD); City of Kenosha; Amtrak

Modes: heavy rail metro; commuter rail; streetcar; intercity rail

Unique routes: 40 (16 Amtrak; 14 Metra; 8 CTA; 1 NICTD; 1 City of Kenosha)

Distinctive stations: Chicago Union Station; Olgilvie Transportation Center; LaSalle Street Station; Millennium Station (see more on all four here); Joliet Union Station

Equipment: CTA L vehicles; Metra trainsets; NICTD South Shore Line trainsets; City of Kenosha PCC streetcars; Amtrak Amfleet trainsets; Amtrak Superliner trainsets; Amtrak Horizon trainsets

Chicago is the first city of American railroading in terms of rail traffic, both historically and currently. Although the nation's first rail lines started on the East Coast, Chicago – and its access to the Great Lakes, the Midwest and the American frontier – was their ultimate objective. At the same time, the railroads shaped Chicago in a way unlike any other American city: long-distance trains brought residents from back east and its commuter and elevated trains helped them move around town once they arrived.

Today, Metra's commuter rail network is the nation's largest in terms of route miles, the CTA's iconic L train is the third-busiest in the U.S. after New York and Washington (with ridership skyrocketing due to recently-rehabilitated lines) and Amtrak operates more distinct intercity and long-distance routes from Union Station than any other place in the country. So why does it come in with 7th place in my rankings? Uniformity.

In terms of moving massive numbers of people reliably and efficiently, uniformity certainly isn't a bad thing. Systems are cheaper to build and operate when they use the same kinds of vehicles and stations to reduce compartmentalization of operators, mechanics, dispatchers and more. But from a rail observer's perspective, once you've experienced one kind of vehicle or station, there's a law of diminishing returns. The essential uniformity of the Washington Metrorail network bumped that region to #10 and it's likely you'll hear something similar about the New York City Subway in the next couple days. Both the CTA L network and Metra's commuter rail system are tremendous assets, but their equipment is essentially standardized and non-terminal stations are largely uniform.

Nonetheless, there are still many interesting quirks for rail fans to enjoy. Chicago's L is as reflective of the city's identity as the Subway is in New York, streetcars are in New Orleans and cable cars in San Francisco. The Loop through downtown – largely from which the El name is derived – is something every urbanist and transit advocate should experience at least once. It's wood-and-steel structures present a somewhat rickety ambiance to first-time observers, but the century-old infrastructure's persistence to this day suggests its anything but shoddy engineering. It's Red and Blue subway lines through the Loop offer a nice contrast to the activity above and the system's routes into the city's neighborhoods are well-woven into the fabric of their communities. And like most of the nation's historic rail networks, it does a phenomenal job in serving all ranges of demographics.

The four-track North Side Main Line (also known as the Howard Branch) is the system's busiest and is thrilling for any train watcher. Between the Brown, Purple and Red lines, it alone carries more than 120,000 daily riders, or more than all the ridership of Dallas' rail transit options put together. At one time, the interurban trains of the Chicago, North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad (aka the North Shore Line) once shared the Howard Branch with L trains to reach the Loop from Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, Waukegan and Mundelein. Today, a hint of that legacy remains with the CTA's Yellow Line – perhaps the best named transit train left today, the Skokie Swift – which travels on the North Shore's former Skokie Valley route to reach its namesake city. Until 2005, Skokie Swift trains were powered via overhead catenary, the only heavy rail application besides Cleveland's Red Line to use overhead power. Third rail power was added that year to allow interoperability with the rest of the L fleet.

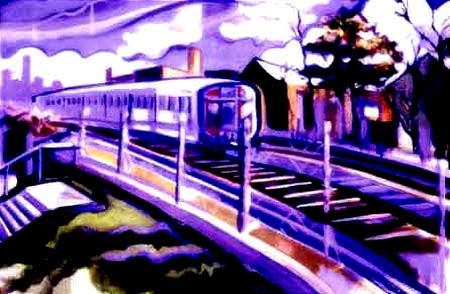

While the North Shore's interurbans disappeared in the early 1960s, its counterpart on the south side of Chicago – the Chicago, South Shore and South Bend Railroad – managed to maintain its passenger service between its namesake cities. The NICTD began subsidizing its passenger operations in 1977 and took control of the service in 1990. It's essentially the North America's last interuban (see into photo), although many of the recently-launched regional rail lines (see examples in the Portland and Dallas Top 10 posts below) operate much like an interuban. Also unique to Chicago is the South Shore's electrified route, along with that of the three branches of Metra's appropriately-named Electric Division. Until Denver's A Line to Denver International Airport opens next spring, the lines are the only electrified railroads (not including rail transit like light rail, streetcars and heavy rail metro) east of Harrisburg, Pa.

Whether coming by intercity or commuter rail, Chicago has the most extensive grouping of passenger rail terminals on the continent. I wrote about the quartet of terminals in this post from 2010, as well as the distinctive 1912 Joliet Union Station about an hour and a half southwest of the Loop by train. It's served by Metra's Heritage Corridor and Rock Island District trains as well as Amtrak's Lincoln Service and Texas Eagle routes. Another interesting sport for train riders is Prairie Crossing in Libertyville, a location I spent some time discussing in this post, also from my 2010 visit.

In this series, I include nearby cities as part of a region when one can take a regularly scheduled commuter or rail transit train between the two places, like Baltimore-Washington and Dallas-Ft. Worth-Denton in the previous posts below. Here, Metra provides service to Kenosha, Wisc., on its Union Pacific–North Line. Kenosha Transit has operated its Electric Streetcar Circulator since 2000 using a fleet of seven painstakingly refurbished PCC cars. The streetcars make a loop through downtown from the Metra station to the Lake Michigan waterfront, a two-mile roundtrip. More than 30 percent of Kenosha visitors use the streetcar route, along with local travelers. Last year, the Kenosha City Council voted to extend the operation running north and south to complement the existing east-west running service. Construction is expected to begin this fall.

There's a host of proposals to expand both L and Metra routes throughout the region, as well as introducing light rail, streetcar and more intercity service along with high-speed rail lines. Beyond the Kenosha streetcar expansion, no other new projects are currently heading for construction anytime soon.

Chicago is the first city of American railroading in terms of rail traffic, both historically and currently. Although the nation's first rail lines started on the East Coast, Chicago – and its access to the Great Lakes, the Midwest and the American frontier – was their ultimate objective. At the same time, the railroads shaped Chicago in a way unlike any other American city: long-distance trains brought residents from back east and its commuter and elevated trains helped them move around town once they arrived.

Today, Metra's commuter rail network is the nation's largest in terms of route miles, the CTA's iconic L train is the third-busiest in the U.S. after New York and Washington (with ridership skyrocketing due to recently-rehabilitated lines) and Amtrak operates more distinct intercity and long-distance routes from Union Station than any other place in the country. So why does it come in with 7th place in my rankings? Uniformity.

In terms of moving massive numbers of people reliably and efficiently, uniformity certainly isn't a bad thing. Systems are cheaper to build and operate when they use the same kinds of vehicles and stations to reduce compartmentalization of operators, mechanics, dispatchers and more. But from a rail observer's perspective, once you've experienced one kind of vehicle or station, there's a law of diminishing returns. The essential uniformity of the Washington Metrorail network bumped that region to #10 and it's likely you'll hear something similar about the New York City Subway in the next couple days. Both the CTA L network and Metra's commuter rail system are tremendous assets, but their equipment is essentially standardized and non-terminal stations are largely uniform.

Nonetheless, there are still many interesting quirks for rail fans to enjoy. Chicago's L is as reflective of the city's identity as the Subway is in New York, streetcars are in New Orleans and cable cars in San Francisco. The Loop through downtown – largely from which the El name is derived – is something every urbanist and transit advocate should experience at least once. It's wood-and-steel structures present a somewhat rickety ambiance to first-time observers, but the century-old infrastructure's persistence to this day suggests its anything but shoddy engineering. It's Red and Blue subway lines through the Loop offer a nice contrast to the activity above and the system's routes into the city's neighborhoods are well-woven into the fabric of their communities. And like most of the nation's historic rail networks, it does a phenomenal job in serving all ranges of demographics.

The four-track North Side Main Line (also known as the Howard Branch) is the system's busiest and is thrilling for any train watcher. Between the Brown, Purple and Red lines, it alone carries more than 120,000 daily riders, or more than all the ridership of Dallas' rail transit options put together. At one time, the interurban trains of the Chicago, North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad (aka the North Shore Line) once shared the Howard Branch with L trains to reach the Loop from Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, Waukegan and Mundelein. Today, a hint of that legacy remains with the CTA's Yellow Line – perhaps the best named transit train left today, the Skokie Swift – which travels on the North Shore's former Skokie Valley route to reach its namesake city. Until 2005, Skokie Swift trains were powered via overhead catenary, the only heavy rail application besides Cleveland's Red Line to use overhead power. Third rail power was added that year to allow interoperability with the rest of the L fleet.

While the North Shore's interurbans disappeared in the early 1960s, its counterpart on the south side of Chicago – the Chicago, South Shore and South Bend Railroad – managed to maintain its passenger service between its namesake cities. The NICTD began subsidizing its passenger operations in 1977 and took control of the service in 1990. It's essentially the North America's last interuban (see into photo), although many of the recently-launched regional rail lines (see examples in the Portland and Dallas Top 10 posts below) operate much like an interuban. Also unique to Chicago is the South Shore's electrified route, along with that of the three branches of Metra's appropriately-named Electric Division. Until Denver's A Line to Denver International Airport opens next spring, the lines are the only electrified railroads (not including rail transit like light rail, streetcars and heavy rail metro) east of Harrisburg, Pa.

Whether coming by intercity or commuter rail, Chicago has the most extensive grouping of passenger rail terminals on the continent. I wrote about the quartet of terminals in this post from 2010, as well as the distinctive 1912 Joliet Union Station about an hour and a half southwest of the Loop by train. It's served by Metra's Heritage Corridor and Rock Island District trains as well as Amtrak's Lincoln Service and Texas Eagle routes. Another interesting sport for train riders is Prairie Crossing in Libertyville, a location I spent some time discussing in this post, also from my 2010 visit.

In this series, I include nearby cities as part of a region when one can take a regularly scheduled commuter or rail transit train between the two places, like Baltimore-Washington and Dallas-Ft. Worth-Denton in the previous posts below. Here, Metra provides service to Kenosha, Wisc., on its Union Pacific–North Line. Kenosha Transit has operated its Electric Streetcar Circulator since 2000 using a fleet of seven painstakingly refurbished PCC cars. The streetcars make a loop through downtown from the Metra station to the Lake Michigan waterfront, a two-mile roundtrip. More than 30 percent of Kenosha visitors use the streetcar route, along with local travelers. Last year, the Kenosha City Council voted to extend the operation running north and south to complement the existing east-west running service. Construction is expected to begin this fall.

There's a host of proposals to expand both L and Metra routes throughout the region, as well as introducing light rail, streetcar and more intercity service along with high-speed rail lines. Beyond the Kenosha streetcar expansion, no other new projects are currently heading for construction anytime soon.

The Most Interesting North American Rail Networks Series